Drake’s Circumnavigating Voyage

Queen Elizabeth quietly invested in Drake’s voyage which set out set out on November 15, 1577, ostensibly as a trading venture to the eastern Mediterranean. He sailed with five ships, the Pelican, Elizabeth, Marigold, Benedict, and Swan. On the morning of the 16th, a violent gale struck the fleet off the Lizard in Cornwall and dismasted the Pelican and Marigold which forced the expedition back to port for repairs. It would be almost three years after this false start before Drake saw England again in September 1580.

Off the northwest Moroccan coast, Drake’s real course became evident: he revealed that the expedition was going to the Pacific Ocean via Brazil and the Strait of Magellan to raid Spanish Colonies. At Port San Julian, Argentina, Drake quashed what he saw as an incipient mutiny at by his second in command, Thomas Doughty, by ordering Doughty to be tried and then beheaded. After sailing from the port, Drake paused at the Strait of Magellan and re-named the Pelican to the Golden Hind possibly as a measure to smooth over the matter with Doughty's mentor, Sir Christopher Hatton whose crest included the hind.

By this time, two ships had been broken up for firewood, and usable material salvaged for future use. Their crews transferred to the other ships. Navigating the Strait proved to be relatively easy, and Drake exited the Strait on September 6, 1578. However—on the next day—the ships encountered a two-month long storm the misnamed Pacific Ocean. The storm cost Drake two of his three ships: one, the Marigold, was overwhelmed by the sea with all hands and a second, the Elizabeth, separated by storms, returned to England. Drake’s Golden Hind was blown so far south and east that he discovered Cape Horn and the open southern ocean. The tempestuous waterway there—which links the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans—is now called Drake Passage. These experiences reveal Drake as a highly skilled, maritime explorer.

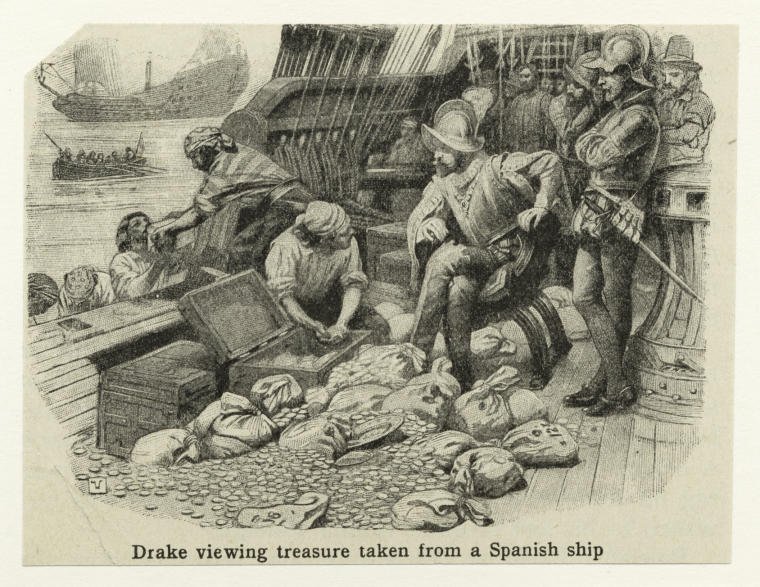

Finally, the storms abated, and Drake sailed north. On December 5, 1578, Drake’s crew looted their first settlement, Valparaiso, Chile. Continuing to raid shore-side settlements and capturing ships along the coast of Chile, Drake usually stayed ahead of warnings of his coming. As was usual in his career, he treated captives well, learned much from them, and sent them on their way in ships which had been stripped of most of their sails. He sailed into Callao, the port of Lima, Peru, and cut the cables of the ships in the harbor so they would float out to sea with wind and tide to prevent pursuit. Captives’ stories of a treasure ship sailing toward Panama sent the Golden Hind in pursuit. Off Ecuador, on March 1, 1579, Drake captured the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción with twenty-six tons of silver bars, thirteen or fourteen chests of pieces of eight, and eighty pounds of gold—valued at half the annual revenues of his queen.

Drake’s last call to a Spanish port was at the small town of Guatulco, a port on the southern coast of Mexico. He remained there from April 13 to 16. After looting the town, Drake knew it was time to begin his journey home. The way south to the Strait of Magellan was likely barred by armed and angry Spaniards. The route west across the Pacific promised typhoons in the East Indies if he sailed at that time of year. Sailing north to find the western entrance to the Strait of Anian—the route to the fabled Northwest Passage through northern North America—seemed worth trying. So the Golden Hind sailed from Guatulco, then fifteen hundred miles northwest out to sea. When the weather became unbearably cold, Drake tacked the Golden Hind high to the northeast in the North Pacific to regain the coast and search for the hoped-for passage. It was not to be—the passage was not there.

With the capture of the Cagafuego treasure galleon on February 15, 1579, Drake purloined wealth equivalent to half of Queen Elizabeth’s annual revenue.

To watch the excellent, 52 minute documentary, Conquest of the Seven Seas: Sir Francis Drake, click HERE.

Wikimedia Commons Images

On June 6 and without going ashore, Drake made landfall at the Oregon Dunes and found that the land trended much farther to the west than he had hoped. There was no strait at that latitude. Relentless northwest winds and cold forced him to turn south after a short anchorage in the insecure South Cove at Cape Arago.

Three hundred miles of sailing along a dangerous rock-bound shoreline with no good harbors and steady onshore winds brought the Golden Hind to within sight of the long Point

Reyes Peninsula jutting into the ocean ahead of the ship. A turn to seaward cleared the beaches and the granite monolith of Point Reyes Head. Then, a sharp turn toward the east carried the ship past the three-mile-long headland and into the shelter of Drakes Bay, where a small cove inside the inner waterway of Drakes Estero provided the secure harbor Drake and his men sought. They needed to repair and resupply the Golden Hind for the trans-Pacific voyage that was the only remaining open route to the Atlantic and England. Francis Drake landed at Drakes Bay, thirty miles north of San Francisco, on June 17, 1579, Drake’s men built a fortified camp, unloaded the Golden Hind and rolled her on one side and then the other to clean and repair her hull, filled the water barrels, and replenished her meat supply by taking and salting deer and seals. Drake’s chaplain held services from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer—the first in this land.

Wikimedia Commons Image

All the while, Drake and his crewmen met with the Coast Miwok people in a friendly but uncomprehending series of interactions, including a ceremony led by a regional chieftain that concluded with Drake’s sitting down to be crowned with a feather headdress and adorned with shell-bead necklaces. Later, Drake marched inland for a day to see the nature of the land, and he made a formal claim to western North America in the name of his Queen Elizabeth—the first English claim to the land that would, in time, become the United States of America.

He named the land Nova Albion, or New Albion, after the great white cliffs which ring Drakes Bay. They reminded the homesick Englishmen of their cliff-girt homeland, England, whose ancient name was Albion. This was America’s original New England.

Thirty-six days after arrival, Drake’s Golden Hind was ready to sail out of the little cove, into the bay, to the Farallon Islands twenty miles to the south, and into the deep Pacific. The voyage continued and led to more adventures: near shipwreck, a trade treaty in the Spice Islands (the Moluccas of eastern Indonesia), a long run across the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, a triumphant return to Plymouth, and a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth on the deck of his Golden Hind, for Sir Francis Drake, the first English circumnavigator.

Wikimedia Commons Images

Further Reading:

• Sugden, John (2006). Sir Francis Drake.

• Turner, Michael (2006). In Drake's Wake Volume 2 The World Voyage.